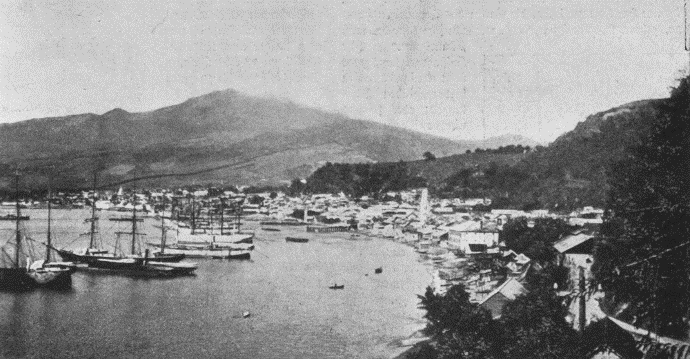

The scorched remains of the steamer SS Roraima smoulders off the Martinique port of St Pierre, hours after the catastrophic eruption of Mount Pelée in the background had annihilated the town and all but a handful of its 30,000 inhabitants. The dozen or so survivors of the passenger ship Roraima, along with those aboard other ships in the harbour lucky enough to survive the events of 8th May 1902, provide dramatic testimony to a disaster that was not only municipal but also maritime.

Situated on the leeward coast of Martinique in the Lesser Antilles, St Pierre was the island’s most culturally and economically important settlement by the end of the 19th century. The port, a centre for coffee, cocoa, sugar cane and rum production, received a steady stream of trading vessels and small passenger steamers, carrying wealthy travellers wishing to experience the so-called ‘Paris of the West Indies’. Dominating the skyline about seven kilometres north of the town stood Mont Pelée, a 4,500ft stratovolcano with a long history of volcanic activity that had earned it the name ‘fire mountain’ from the indigenous Carib people. Under French rule there had been significant phreatic (steam) eruptions in 1794 and 1851, but until the events of 1902, the residents of St Pierre, and visiting ships, had had more to fear from Caribbean meteorology than its geology. A 25ft storm surge during the ‘Great Hurricane’ of 1780, for example, had inundated the town and killed an estimated 9,000 residents. As the quiescent mountain stirred into life in the middle of 1900, neither residents nor those offshore had any comprehension of the peril it posed.

The prelude to Mont Pelée’s major eruption began in January 1902 with an observed increase in fumarole activity, toxic gas emissions around a caldera known as Etang Sec. However, little attention was paid to the mountain until 23rd April when more significant signs were observed. Small explosions occurred around the summit and the town was rocked by earth tremors, and smothered in ash and clouds of sulphurous gas. On 5th May, a lahar caused by the release of boiling water and debris from Etang Sec cascaded down the River Blanche, overflowing its banks and burying the 23 workers of a rum distillery just north of the town. As the scalding mudflow entered the sea it caused a tsunami that inundated the waterfront. These events led to an influx of refugees from outlying settlements, as well as an invasion of snakes and other ground-dwelling fauna from the surrounding slopes. Ash-covered birds were reported falling dead from the sky, fish floating dead in the harbour.

Despite mounting evidence of peril, the St Pierre authorities remained sanguine. These were led by Governor Louis Mouttet, whose party was expected to prevail in the local elections due to be held on 11th May. A committee despatched to investigate the risks of eruption ignorantly, and perhaps conveniently, concluded that the mountain posed no direct threat to the town, the two being safely separated, it was determined, by ‘immense valleys’. These views were relayed to the populace through a politically compliant local press. While many people chose to flee, others trusted in the safety of numbers, and the surety of urban bricks and mortar. As one wealthy resident resignedly wrote, ‘If death awaits us, there will be a numerous company in which to leave the world.’

A photo taken days before the disaster shows the Bay of St Pierre crowded with shipping. Among the vessels known to have been in port on 8th May were two Italian sailing barks, the Nord America and Teresa lo Vico, a French square-rigger Tamaya, and the Diamant, a small steam packet which ferried passengers to and from the administrative capital Fort-de-France.[1] Anchored close to shore was the cable-ship Grappler. Built by James Laing of Sunderland, this 870t vessel flew the distinctive blue and white flag of the West India and Panama Telegraph Company.[2] Grappler was one of two cable-ships then attempting to repair submarine cables damaged by the recent volcanic activity. Out at sea that morning was the other. Belonging to the Companie Française des Cables Télégraphiques, the 1,360grt Pouyer Quertier had been constructed by C. Mitchell & Co. of Tyneside, a specialist in cable-laying vessels.

Arriving in St Pierre around sunrise on the day of the catastrophe were two larger iron steamers. The Roddam was a cargo carrier of 2,378grt. She’d been built in 1887 by Edward Witty & Co. of Hartlepool. She was owned by Steel, Young & Co., another Hartlepool company whose ships were recognised by their red, white-striped funnels. The largest vessel in port and the last to arrive was the Roraima. Weighing 2,712grt, and 103m long, she’d been built in 1883 by Clyde shipyard Aitken and Mansel. A handsome ship with two raked masts and raised decks amidships and on her poop, she had spent the first 17 years of her service as the SS Ghazee of the Bombay & Persia Steamship Co. Her then owners were the Quebec Steamship Company, which ran a regular service between New York and the Windward Islands. Roraima’s single funnel was painted red and at her stern flew the company pennant – a blue vertical cross and a white horizontal one on a red background.

One ship scheduled to be in port on that fateful morning was the Italian bark Orsolina. The ship had in fact left the roadstead the previous day with only half her authorised cargo of sugar left on the dockside, a decision taken by her nervous Neapolitan captain Marina Le Boffe. Outraged port officials had threatened to have Le Boffe arrested, but he had ignored their threats. ‘I know nothing about Mt. Pelée’, he reportedly told them, ‘but if Vesuvius were looking the way your volcano looks this morning, I’d get out of Naples!’ Le Boffe’s words would prove tragically prophetic.

The summit of Mont Pelée continued to erupt as St Pierre and the ships in its harbour stirred into life at sunrise on 8th May. Assistant purser Thompson observed ‘the rolling and leaping of the red flames that belched from the mountain’ as the Roraima entered the Bay of St Pierre, accompanied by a ‘constant muffled roar’. It was, he related after the disaster, a ‘magnificent spectacle.’ ‘The volcano… engaged the attention of all on board’, wrote First Mate Ellery Scott. ‘Smoke was pouring upward from the crater, and it was impossible to see the summit, for the wreathing smoke concealed it. We felt some uneasiness, and said so when the agents came on board.’ Clara King, nanny to the three children of an American widow Mrs Clement Stokes, overheard a conversation on deck between her mistress and the Roraima’s Captain Muggah. ‘I’m not going to stay any longer than I can help’, muttered the clearly unnerved skipper. King and Mrs Stokes went below deck soon afterwards to join the other passengers for breakfast. About 8km offshore, on the deck of the Pouyer Quertier,ship’s doctor Emile Berte had just completed a medical inspection of the cable-layer’s crew. The time according to the clock on the facade of St Pierre’s military hospital read 07.52am.